Ken Brewer died on Wednesday at the age of 64. The cause? Pancreatic cancer, with which he was diagnosed only last June. Evidently, his response to the news that he had this deadliest, most incurable of cancers was to take up his pen and write. He spent the last months of his life writing poetry at a rate he described as a “fever pitch.” Ironically, after a lifetime of writing poetry, it is these death poems – written, I suppose, in the spirit of Dylan Thomas, who himself advised poets to "rage, rage against the dying of the light" – that have given Ken Brewer his fifteen minutes of fame. I think, from what little I’ve seen of his work, that he deserves a good deal more fame than that – but we’ll see if the world accords him more than passing notice.

Ken Brewer died on Wednesday at the age of 64. The cause? Pancreatic cancer, with which he was diagnosed only last June. Evidently, his response to the news that he had this deadliest, most incurable of cancers was to take up his pen and write. He spent the last months of his life writing poetry at a rate he described as a “fever pitch.” Ironically, after a lifetime of writing poetry, it is these death poems – written, I suppose, in the spirit of Dylan Thomas, who himself advised poets to "rage, rage against the dying of the light" – that have given Ken Brewer his fifteen minutes of fame. I think, from what little I’ve seen of his work, that he deserves a good deal more fame than that – but we’ll see if the world accords him more than passing notice.I haven’t heard of Brewer’s work before – and, in fact, as with too many poets, it seems that most of his books are out of print. It’s also frustratingly hard to find any of his poetry online – just snippets here and there.

I do discover a feature story that CBS News did on him back in December. It includes a couple of video clips of him reading his poetry. One of the poems he read to the television camera I decide to write down. Here it is (although, because I’ve transcribed it from oral form, the punctuation and line breaks may not be quite as the poet intended):

“The Measure”

by Kenneth Brewer

I measure my life in friends

and I am humbled by the numbers,

the quality,

the style, path, policy and grace.

I measure my life in days

when friends write,

when we converse as they sit by my bed,

read poems and listen.

I measure my life in family

who speak through tears,

who serve me meals on a wicker tray,

who pray and love and float.

I measure my life in pine siskens

who entertain me in feeders outside my window,

and Gus, the schnauzer,

who curls next to me in bed.

I measure my life in friends

who do not know my sins,

who hug my shrunken body,

who break open my heart with words.

I measure my life in cancer

that has taught me how to measure my life.

He’s right about that. Cancer – for those of us who have it – does have a way of teaching us how to measure our lives. I suppose that many of those, like Ken Brewer, who are unfortunate enough to have one of the deadliest types of cancer, achieve a certain clarity of purpose right quickly. They have heard their doctor soberly say, “Go put your affairs in order.” And so they do. If the person is a poet, then that may mean, “Go write more poems.”

In reading a news article about him, I discover another thing Ken Brewer said, something he had learned about cancer:

“Brewer experienced an evolution of language as he wrote about cancer. He noticed all the ‘military terms,’ such as ‘fight, battle, kill,’ and he used those in his early poems. But gradually he came to feel that he should talk about cancer in a different way. ‘It’s your cancer – a house guest who stays longer than you wanted him to. You kill your spirit when you use military language. There are other parts of you that need to be healed. I focus now on spiritual healing.’”

(Dennis Lythgoe, “Utah Poet Writes at a Fever Pitch,” Deseret Morning News, December 18, 2005)

I’ve been using that military language some, in talking about my own cancer. It’s hard not to. A lot of the stuff written about cancer treatment – the “War on Cancer” – does talk about “attacking” the malignant cells, about “killing”them. I’ve heard Rituxan, the medicine I’m taking, described as a “smart bomb” that goes right to the cancer cells and obliterates them. There’s a sort of righteous rage behind that choice of words (“Yes, officer, I confess: I killed that cancer cell, but you have to understand, I did it in self-defense”).

I’ve been using that military language some, in talking about my own cancer. It’s hard not to. A lot of the stuff written about cancer treatment – the “War on Cancer” – does talk about “attacking” the malignant cells, about “killing”them. I’ve heard Rituxan, the medicine I’m taking, described as a “smart bomb” that goes right to the cancer cells and obliterates them. There’s a sort of righteous rage behind that choice of words (“Yes, officer, I confess: I killed that cancer cell, but you have to understand, I did it in self-defense”).Ken Brewer figured out, over time, that the military language wasn’t doing him any good. Cancer, after all, is not some foreign microbe that infiltrates our bodies and sets up housekeeping like an unwelcome squatter. Cancer is our bodies. It is our very own cells, whose mutinous growth has been mapped out in advance by rebel strands of our own DNA. Certain cancers, it seems, are pre-programmed into our bodies at birth. If we live long enough, eventually our genetic code will trigger the mutation, and the disease will be off and running.

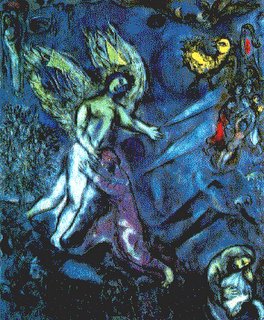

So does it make sense to speak of “killing” the cancer, to blow those errant cells to smithereens? I’m not sure it does – as emotionally satisfying as it may seem, at times, to vent our anger in such a way. If what I’ve learned about lymphoma is correct, then I’m probably going to have the disease the rest of my life. It’s part of me, and always will be. If Ken Brewer’s right, then maybe I need to embrace it – although I suppose that embrace could be a wrestler’s grip, like Jacob’s at the fords of the Jabbok:

“Jacob was left alone; and a man wrestled with him until daybreak. When the man saw that he did not prevail against Jacob, he struck him on the hip socket; and Jacob’s hip was put out of joint as he wrestled with him. Then he said, ‘Let me go, for the day is breaking.’ But Jacob said, ‘I will not let you go, unless you bless me.’” (Genesis 32:24-26)

“Jacob was left alone; and a man wrestled with him until daybreak. When the man saw that he did not prevail against Jacob, he struck him on the hip socket; and Jacob’s hip was put out of joint as he wrestled with him. Then he said, ‘Let me go, for the day is breaking.’ But Jacob said, ‘I will not let you go, unless you bless me.’” (Genesis 32:24-26)Genesis portrays the solitary figure of Jacob, silhouetted against the rising sun, limping away from that mysterious encounter – but the wiser for it. Cancer may indeed leave us limping, but if we’re canny and persistent, perhaps we can wrestle a blessing out of it after all.