Second opinions are a fine thing, but what does a patient do when the two doctors differ on what must be done?

Second opinions are a fine thing, but what does a patient do when the two doctors differ on what must be done?This is the question on our minds as Claire and I walk into Dr. Lerner’s office, CT scan and PET scan films in hand. In declining to recommend radiation treatments for me, Dr. Portlock seems headed in a slightly different direction than Dr. Lerner. How will he respond when we tell him?

Before I see the doctor, I must first see the nurses (this is standard procedure at Atlantic Hematology/Oncology). Not only am I due for a regular blood draw today, it’s also time for my implanted port to be flushed (a simple procedure, in which an anti-clotting solution is injected into my port, to keep it open and functioning normally). As part of the same procedure, the nurse draws a blood sample right through the port, thus sparing me a second needle stick.

Moments later, Claire and I are sitting in an examining room, waiting for Dr. Lerner, who shows up shortly. He’s interested in what Dr. Portlock had to say yesterday, and we tell him about each of the “4 Rs.” He concurs with her on two of these points: the fact that I’m now in remission, and the fact that long-term maintenance treatments with Rituxan are not advisable.

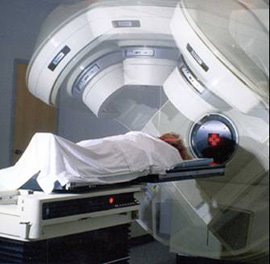

He expresses mild surprise, though, at Dr. Portlock’s judgment that radiation is not the best strategy. Generally, he explains, he recommends radiation for patients like me, who have bulky tumors that were 10 cm or greater in size before the start of treatment. The reason is that, should the cancer ever come back, it’s likely to appear in lymph nodes in the same general area where it appeared previously.

He supposes Dr. Portlock’s decision may have something to do with my initial pathology report, which identified both large (aggressive) and small (indolent) lymphoma cells. If she’s judging that the smaller cells predominate, it’s very possible that a “watch and wait” strategy makes the most sense. He’s been thinking more in terms of the aggressive larger cells, he tells us.

I tell him that Dr. Portlock invited us to have him call her, and he says he will.

The other item is the nodular growth in my right lung. Dr. Lerner takes out the CT scan films one by one, and scrutinizes them using a lighted display panel hanging on the wall. After examining these in silence, he tells us he’s “not very impressed” by the nodular growth. Reading over the radiologist’s report again, he reassures us that it’s not something we should worry about. Still, he concurs with Dr. Portlock that a pulmonologist ought to have a look at the pictures, as a precaution. He recommends I see Dr. Gustavo De La Luz, the local doctor I already see for my sleep apnea.

While he doesn’t say so directly, it becomes plain that Dr. Lerner is no longer planning on referring me for radiation treatments. My next appointment with him, he says, ought to be three months from now, just after I’ve undergone additional CT and PET scans. When we ask him if he’s sure about that, he says yes – but he’d still like to speak directly with Dr. Portlock before making a final decision. If we don’t hear from him differently, he says, we can assume that a three-month appointment it is. If he decides to stick with his earlier prescription for radiation treatments, he’ll let us know, so we can come in and see him sooner.

As Claire and I leave the office, we stop at the front desk and make the appointment for late August. On our way home, we stop for lunch at a local restaurant, the Java Moon Café, and talk together about how quickly things have changed for us. Just a few days ago, we were looking at the prospect of possibly debilitating radiation treatments for me, that would last well into the summer. Now, that blessed word “remission” is in the air, and we’re looking at a much earlier return to normalcy.

It begins to dawn on me that I’m entering a new phase of cancer survivorship. In the weeks and months to come, we’ll certainly celebrate my newfound freedom from the worst side effects of cancer treatment; but we’ll also begin to experience the new reality of wondering when – or if – the cancer may come back.

It begins to dawn on me that I’m entering a new phase of cancer survivorship. In the weeks and months to come, we’ll certainly celebrate my newfound freedom from the worst side effects of cancer treatment; but we’ll also begin to experience the new reality of wondering when – or if – the cancer may come back.But that’s a problem for another day. Right now, the word “remission” is on our lips. And what a good word it is!